The day Science gave me a villilan and it started with a What if. . .

Every once in a while, you stumble across something that makes you stop reading and just… stare at the page for a moment.

That’s what happened years ago when I was flipping through Discover magazine and landed on an article about metamaterials. I wasn’t researching a book. I wasn’t outlining a plot. I was just curious.

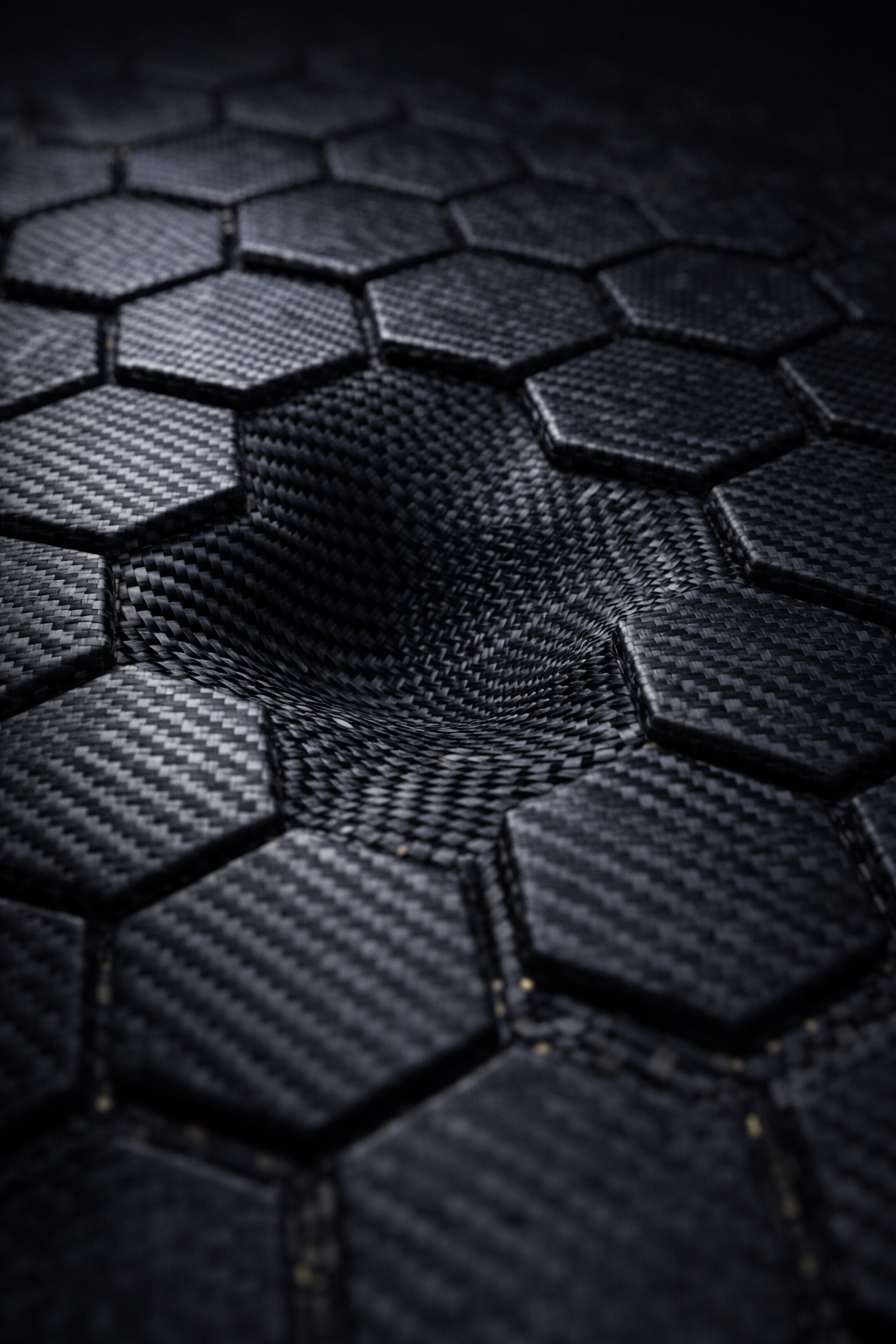

The article explained that metamaterials are different from ordinary materials in one crucial way: they aren’t defined by what they’re made of, but by how they’re structured. At a microscopic scale—smaller than the wavelength of radiation itself—these materials can influence how electromagnetic waves behave. Not block them. Not shield against them in the traditional sense. But control them. Radiation could be bent. Redirected. Slowed. Guided around an object. In some cases, absorbed so completely that it didn’t reflect back at all.

And my very first thought wasn’t about danger. It was about possibility.

The “good intentions” version:

What if a scientist set out to use this kind of material for protection?

Radiation is everywhere in modern life. Medical imaging. Cancer treatments. Power generation. Space exploration. Entire industries exist to measure, manage, and mitigate exposure.

A material engineered to accept radiation instead of scattering it could be revolutionary. Imagine medical equipment where radiation exposure is dramatically reduced—not because it’s blocked, but because it’s quietly absorbed and dissipated inside the material. Imagine nuclear facilities with additional layers of safety—materials that prevent radiation leaks from ever producing a detectable signature in the first place.

That’s not fantasy. That’s a very reasonable extension of what scientists were already experimenting with in the mid-2000s. Metamaterials were showing that radiation doesn’t have to bounce back to exist. It can be handled.

And that’s when my writer brain, inevitably, leaned in.

The uncomfortable follow-up question:

Because once you accept that radiation can be absorbed and internally redistributed, another question follows naturally: What happens to detection?

Most radiation sensors don’t “see” objects. They read returns—reflections, scatter, predictable responses. If radiation enters a material and doesn’t come back in a recognizable way, the sensor doesn’t register an anomaly. From the instrument’s point of view, nothing is there.

That’s when the story shifted.

What if someone realized that the same material designed to make hospitals safer or power plants more secure could also be used to hide things? What if radiation detectors—the systems meant to stop dangerous materials from moving through the world—were rendered useless simply because the radiation never behaved the way the sensors expected?

That’s the pivot point in the book.

Not because the science is evil. But because science, by itself, is neutral.

The real science, simply put:

Here’s what metamaterials in the real world can already do:

They can be engineered so incoming radiation doesn’t reflect

They can match the electromagnetic “impedance” of open space, preventing detectable echoes

They can convert radiation energy into other forms inside the material

They can suppress secondary signatures like scatter or localized heating

In laboratory settings, each of these capabilities exists independently.

What fiction allows—and what my story explores—is the idea of those principles being combined, refined, and stabilized into a single material that works reliably outside the lab.

A material that doesn’t block radiation. Doesn’t announce its presence. Doesn’t trigger alarms.

It simply… absorbs.

Where fiction steps in:

The metamaterial in the book isn’t magic. It doesn’t make radiation disappear. The energy still exists—it’s just redistributed internally in ways detection systems aren’t designed to interpret.

The speculative leap is imagining what happens when:

the material becomes portable

the process becomes scalable

and someone realizes it can be used for concealment, not just protection

That’s where the story lives.

Between good intentions and bad outcomes.

Between discovery and misuse.

Between what we meant to build and what it becomes.

Why this kind of science fascinates me:

I’m drawn to ideas that start with hope.

A scientist trying to make something safer.

A material designed to protect rather than harm.

A breakthrough that looks, at first glance, like nothing but progress.

Because those are the ideas most worth interrogating.

The metamaterial in this book began as a quiet “what if” sparked by a real article, real research, and a moment of genuine curiosity.

And then—inevitably—it turned into another question entirely:

What if someone else asked a different question… and liked the answer a little too much?